Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a brutal stress test for the global supply chains that underpin the modern American economy, exposing critical vulnerabilities that had been baked into decades of optimization for low cost and efficiency above all else. The resulting disruptions—empty shelves, port backlogs, and soaring freight costs—were not a temporary breakdown but a systemic failure of a fragile, hyper-globalized model. This analysis delves into the post-pandemic re-architecting of US manufacturing and logistics networks, a transformation now centered on the imperative of resilience. We examine the strategic shift from “just-in-time” to “just-in-case,” analyzing the key pillars of this new paradigm: nearshoring and friendshoring, inventory and warehouse strategy overhauls, massive technological digitization, and workforce modernization. The report concludes that while the journey is complex and costly, the move towards more regionalized, diversified, and intelligent supply chains is not a transient trend but a permanent and necessary recalibration. For US businesses, building resilient supply chains is no longer a tactical option but a strategic mandate for survival and competitive advantage in an era of persistent volatility.

1. Introduction: The Great Fragility Revealed

For decades, the dominant paradigm in global supply chain management was relentlessly focused on leanness and efficiency. Driven by the principles of “Just-in-Time” (JIT) inventory management, companies engineered intricate, globe-spanning networks that minimized carrying costs and capitalized on low-cost labor. This model delivered unprecedented consumer choice and corporate profitability. However, it also created a system of breathtaking fragility, where a disruption in a single node—a factory in Wuhan, a port in Los Angeles—could trigger cascading failures across the entire network.

The pandemic ripped away the veil, revealing the profound risks of this extreme interdependence. It was followed by a series of other shocks—geopolitical tensions, climate-related disasters, and the war in Ukraine—that cemented the understanding that volatility is the new constant. This report provides a post-pandemic analysis of how US manufacturing and logistics networks are being fundamentally reimagined and rebuilt. We will explore the death of pure JIT, the rise of new strategic frameworks like “China Plus One” and nearshoring, the critical role of technology in creating visibility, and the human capital required to manage this new, more complex ecosystem. The central thesis is that the pursuit of resilience—the ability to anticipate, withstand, and recover from disruptions—has become the North Star for American industry.

2. The Pre-Pandemic Paradigm: The Age of Hyper-Efficiency and Its Fault Lines

To understand the present transformation, one must first appreciate the architecture of the past.

2.1 The “Just-in-Time” (JIT) Doctrine

Pioneered by Toyota, JIT aimed to eliminate waste by receiving goods only as they are needed in the production process. This minimized inventory costs and freed up capital. Its success, however, relied on a set of assumptions that proved dangerously optimistic:

- Perfect Stability: Predictable demand and flawless transportation.

- Frictionless Trade: Minimal geopolitical interference and open borders.

- Reliable Partners: Suppliers that never experienced their own disruptions.

2.2 The Offshoring Exodus

Beginning in the late 20th century, US manufacturers embarked on a massive offshoring wave, primarily to China. The drivers were compelling:

- Dramatically Lower Labor Costs

- Expansion into New Markets

- Access to Sophisticated Manufacturing Hubs (e.g., Chinese electronics clusters)

This created elongated, complex supply chains. A single product might involve raw materials from South America, components from Southeast Asia, assembly in China, and final sale in the United States.

2.3 The Hidden Vulnerabilities

This hyper-efficient model created a web of hidden risks:

- Single Points of Failure: Over-reliance on a single geographic region or even a single supplier for critical components.

- Lack of Visibility: Most companies had limited to no real-time visibility into the status of their goods once they left a supplier’s dock.

- Inflexibility: Long lead times made it nearly impossible to quickly pivot in response to demand shocks or supply disruptions.

- The Bullwhip Effect: Small fluctuations in consumer demand caused exponentially larger swings in orders up the supply chain, as each actor amplified the signal to protect themselves.

The pandemic did not create these vulnerabilities; it exploited them with devastating effectiveness.

3. The Pandemic Shock: A System in Crisis

The years 2020-2022 served as a real-time autopsy of a broken system.

- Supply Shock: Factory lockdowns in Asia and elsewhere halted the production of everything from semiconductors to apparel.

- Demand Shock: Pandemic spending patterns shifted violently away from services (travel, dining) to goods (home office equipment, fitness gear), overwhelming logistics networks designed for different volumes.

- Logistical Collapse: A perfect storm hit US ports. A shortage of shipping containers, a lack of warehouse space, truck driver shortages, and labor disputes created historic backlogs. The cost to ship a container from Asia to the US West Coast skyrocketed by over 500% at its peak.

- The Inventory Crisis: The JIT model collapsed. Companies with lean inventories found their shelves empty, leading to lost sales and eroding customer trust.

This crisis made it undeniably clear that the cost of disruption far outweighed the savings of lean inventory.

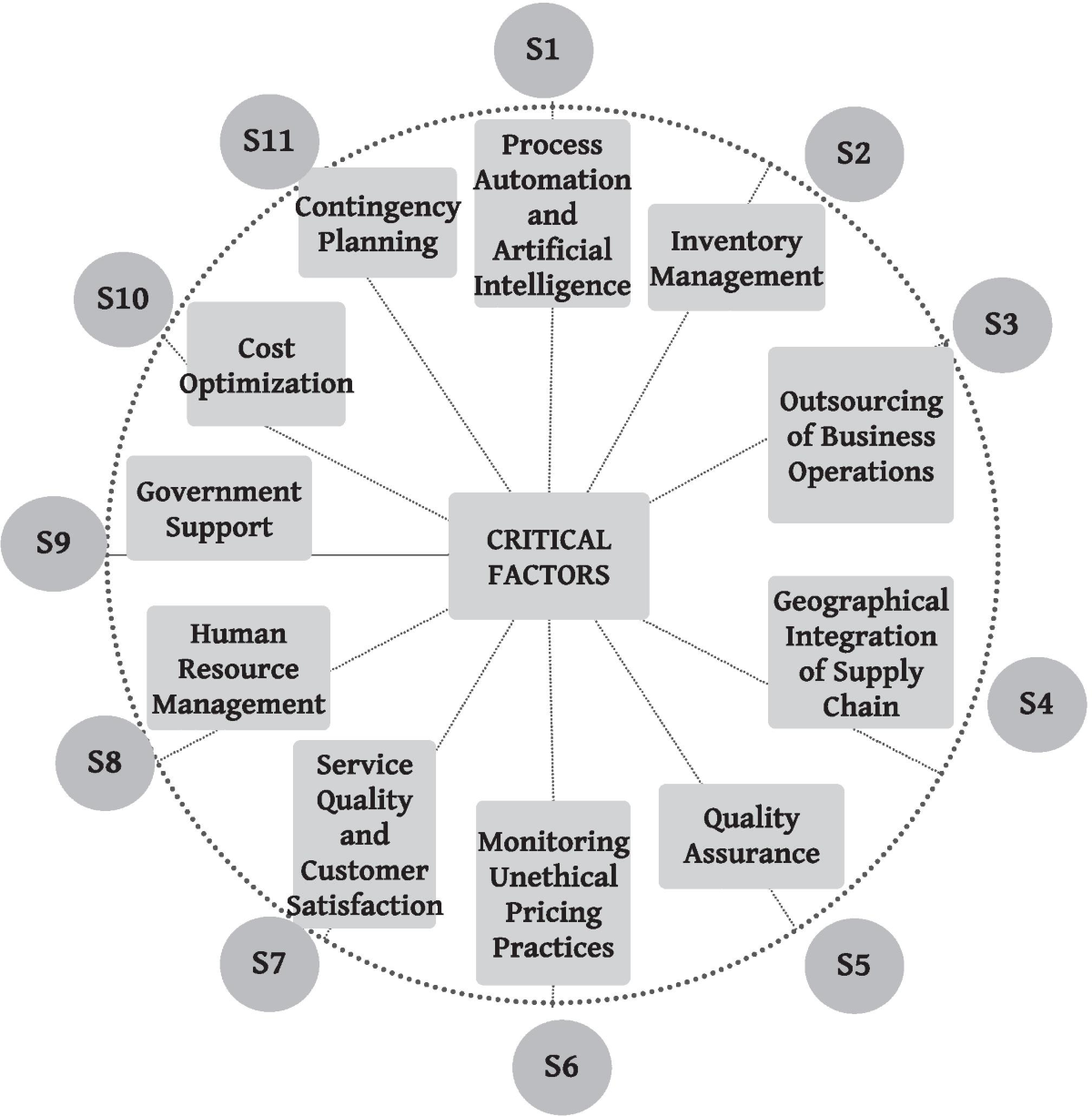

4. The Pillars of Post-Pandemic Resilience

In response, a new supply chain architecture is being built, resting on four core pillars.

4.1 Strategic Rebalancing: Reshoring, Nearshoring, and Friendshoring

The most significant strategic shift is the geographical reconfiguration of sourcing and manufacturing.

- Reshoring: Bringing manufacturing and supply chains back to the United States. This is often driven by government incentives (like the CHIPS and Science Act), the need for stricter IP protection, and the value of proximity to the end consumer.

- Example: Intel’s massive investment in new semiconductor plants in Ohio and Arizona.

- Nearshoring: Moving production to nearby countries, notably Mexico and Canada. This reduces transit time, lowers exposure to geopolitical risks in Asia, and benefits from free trade agreements like the USMCA.

- Example: Tesla’s gigafactory in Monterrey, Mexico, supplying the US EV market.

- Friendshoring (or Allyshoring): Diversifying supply networks across politically aligned countries to de-risk from geopolitical tensions. This involves shifting sourcing from adversaries to trusted partners in regions like India, Vietnam, and Eastern Europe.

- Example: Apple actively encouraging its suppliers to expand production capacity in India and Vietnam alongside China.

The goal is not total autarky, but a balanced, diversified portfolio that reduces over-concentration in any one region.

Read more: Beyond Silicon Valley: An Analysis of Emerging Tech Hubs and Talent Pools Across the United States

4.2 Inventory and Warehouse Strategy: From “Just-in-Time” to “Just-in-Case”

The dogma of lean inventory has been replaced by a more pragmatic approach.

- Strategic Stockpiling: Companies are identifying critical components with long lead times or single-source dependencies and holding safety stock for them. This acts as a “shock absorber” during disruptions.

- The Rise of the “Warehouse Everywhere” Model: To support e-commerce and provide flexibility, companies are investing in a distributed network of warehouses, including:

- Traditional Distribution Centers: Large, regional hubs.

- Fulfillment Centers: For fast e-commerce order processing.

- Micro-Fulfillment Centers: Small, automated warehouses located in or near urban areas to enable same-day and instant delivery.

- The “Dual Sourcing” Mandate: For essential items, companies are actively developing and qualifying a second, and sometimes third, supplier to ensure continuity if a primary supplier fails.

4.3 Digital Transformation and Supply Chain Visibility

You cannot manage what you cannot see. The most significant technological leap is the pursuit of end-to-end visibility.

- AI and Predictive Analytics: Machine learning algorithms are now used to predict demand more accurately, optimize shipping routes in real-time, and identify potential disruptions before they occur by analyzing vast datasets (weather, news, geopolitical events).

- Internet of Things (IoT): Sensors on containers, pallets, and individual products provide real-time data on location, temperature, humidity, and shocks. This allows for proactive management of goods in transit.

- Cloud-Based Platforms: Companies are moving away from siloed, legacy systems to integrated cloud platforms that provide a single source of truth for inventory, orders, and shipments across the entire network.

- Blockchain for Provenance: While still emerging, blockchain technology is being piloted to create tamper-proof records of a product’s journey, crucial for industries like pharmaceuticals and high-value goods where authenticity is paramount.

4.4 Workforce and Partnership Evolution

A more complex supply chain requires a more sophisticated workforce and deeper partner relationships.

- The New Supply Chain Professional: The role has evolved from a logistical function to a strategic one. Companies now seek professionals with skills in data analytics, risk management, cybersecurity, and international relations.

- Upskilling the Frontline: Investing in training for warehouse workers on using automation (robotics, warehouse management systems) and for truck drivers on telematics and route optimization software.

- Collaborative Partnering: The old adversarial, cost-squeezing model with suppliers and logistics providers is giving way to true partnerships. Companies are sharing data and forecasts and even co-investing in resilience measures with their key partners, recognizing that their resilience is interdependent.

5. The Government’s Role: Policy as a Catalyst

The US government has become an active participant in reshaping supply chains, framing the issue as one of national and economic security.

- The CHIPS and Science Act: Provides $52 billion in subsidies for US semiconductor research and manufacturing, directly addressing a critical point of failure exposed during the pandemic.

- The Inflation Reduction Act: Includes massive incentives for domestic production of clean energy technologies (EVs, batteries, solar panels), creating a powerful pull for reshoring in these sectors.

- Supply Chain Resilience Programs: The Biden administration has launched initiatives through the Department of Commerce and other agencies to map critical supply chains, identify vulnerabilities, and fund projects that strengthen US industrial base resilience.

6. Challenges on the Path to Resilience

This transformation is not without its significant headwinds.

- The Cost Conundrum: Resilience is expensive. Holding more inventory, diversifying suppliers, and reshoring production all increase costs. The central challenge for businesses is to balance resilience with profitability and consumer price sensitivity.

- Infrastructure Limitations: Reshoring and nearshoring strain existing US infrastructure. Ports, roads, and the electrical grid require significant investment to support a renaissance in domestic manufacturing.

- The Skilled Labor Shortage: The US faces a chronic shortage of skilled manufacturing workers, truck drivers, and logistics planners, which could throttle the pace of reshoring.

- Geopolitical Complexity: Friendshoring is not a simple solution. It requires navigating a new set of political risks, trade agreements, and logistical challenges in unfamiliar countries.

7. The Future Outlook: The Agile, Adaptive, and Autonomous Supply Chain

The supply chain of the future will look radically different from its pre-pandemic predecessor. Key trends will define the next decade:

- The Permanence of Hybrid Models: The future is not “all reshored” or “all globalized.” It is a hybrid, multi-tiered model that strategically allocates production based on a product’s criticality, cost, and risk profile.

- The Rise of the “Sense-and-Respond” Network: With full visibility and AI-driven analytics, supply chains will become proactive and self-correcting, automatically rerouting shipments or adjusting production schedules in response to real-world events.

- Advanced Automation and Robotics: From autonomous trucks and ships to fully lights-out warehouses, automation will be key to making reshored manufacturing cost-competitive and addressing labor shortages.

- Sustainability and Resilience Converge: Companies are discovering that resilient supply chains are often more sustainable. Shorter shipping distances reduce carbon emissions, and greater transparency ensures ethical and environmentally sound practices.

8. Conclusion: Resilience as the New Competitive Advantage

The pandemic was a painful but necessary catalyst for change. It forced a long-overdue reckoning with the inherent fragility of a supply chain model that prioritized cost savings above all else. The post-pandemic analysis reveals an American industrial landscape in the midst of a profound and permanent transformation.

The journey towards resilience is a marathon, not a sprint. It requires significant capital investment, strategic foresight, and a cultural shift within organizations. However, the businesses that treat this not as a cost center but as a strategic imperative will build a formidable competitive advantage. They will be the ones who can maintain operations and serve their customers when the next disruption—whether a pandemic, a geopolitical conflict, or a climate event—inevitably occurs. In the 21st century, a resilient supply chain is no longer a back-office function; it is the bedrock of a secure, stable, and prosperous American economy.

Read more: 7 Powerful Ways AI Is Reshaping Trading Strategy in 2025 (And What Traders Must Know)

FAQ Section

Q1: Will reshoring mean everything will be “Made in the USA” again and that products will be higher quality?

Not exactly. The goal of reshoring and nearshoring is strategic diversification, not complete self-sufficiency. Certain critical industries (semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, EV batteries) are being prioritized for national security reasons. For many consumer goods, a total reshoring is not economically feasible. The outcome will be a mix: some products will be made domestically, many will come from nearshored locations like Mexico, and others will still come from a more diversified set of Asian partners. As for quality, US manufacturing is highly advanced, but the primary driver is resilience and control, not necessarily a universal leap in quality.

Q2: As a small or medium-sized business (SMB), how can I possibly afford to make my supply chain more resilient?

SMBs can take pragmatic, scalable steps without massive investment:

- Diversify Your Suppliers: Start by finding a backup for your single most critical component.

- Increase Communication: Have deeper conversations with your key suppliers about their own risks and continuity plans.

- Hold Strategic Inventory: Analyze your product line and identify the 20% of items that generate 80% of your profit. Consider holding slightly more safety stock for these key SKUs.

- Leverage Technology: Subscribe to affordable, cloud-based supply chain visibility software that can track your shipments and provide early warnings of delays.

- Explore Cooperative Purchasing: Partner with other non-competing SMBs to aggregate purchasing power and secure better terms and reliability from shippers and suppliers.

Q3: Has the situation at the ports (like Los Angeles and Long Beach) actually improved?

Yes, significantly. The historic backlogs and record-high shipping costs of 2021-2022 have largely normalized. This is due to a combination of factors: a softening of consumer demand for goods, increased efficiency at the ports (through expanded hours and better coordination between stakeholders), and a rebalancing of global shipping capacity. However, the underlying fragility remains; the next major demand surge or labor dispute could quickly create new bottlenecks.

Q4: What is the single most important thing a company can do right now to improve resilience?

Gain Visibility. The foundational step for all other resilience strategies is to know where your goods are, in what quantity, and their status at every stage of the journey—from raw material to end customer. Investing in technology and processes that provide this end-to-end visibility is the non-negotiable first step. Without it, you are making critical decisions in the dark.

Q5: How does the push for sustainability (ESG) fit with the push for supply chain resilience?

They are increasingly aligned and mutually reinforcing. A resilient supply chain is often a more sustainable one:

- Reduced Emissions: Nearshoring and reshoring shorten transportation distances, directly lowering carbon emissions.

- Ethical Sourcing: Diversifying away from regions with poor labor or environmental records towards partners with stronger regulations improves your ESG profile.

- Reduced Waste: More accurate demand forecasting and inventory management leads to less overproduction and waste.

Companies are now looking at resilience and sustainability through a single, integrated lens, recognizing that a supply chain that is vulnerable to climate change or social unrest is neither sustainable nor resilient.

Disclaimer: This market analysis is based on current data, industry trends, and policy developments as of 2024. The global logistics and manufacturing landscape is highly dynamic and can be affected by new geopolitical events, economic shifts, and technological breakthroughs. This report is intended for informational and strategic planning purposes. Companies should consult with supply chain, legal, and financial professionals for specific advice.

Read more: The US Labor Market Under a Microscope: Analyzing Remote Work’s Lasting Impact and the Skills Gap