The question, “How much do I need to retire?” is one of the most profound and daunting financial questions we face. It’s not just a number-crunching exercise; it’s a deeply personal inquiry into the future you envision for yourself and your loved ones. For decades, a simple concept known as the “4% Rule” has served as the North Star for millions of retirees and financial planners navigating this complex terrain.

But is this decades-old rule still relevant in today’s world of volatile markets, longer lifespans, and low initial bond yields? The answer is both yes and no. The 4% rule is an excellent starting point—a powerful framework for initial conversations. However, treating it as an immutable law is a recipe for potential hardship or missed opportunity.

This article will serve as your definitive guide. We will demystify the 4% rule, explore its origins and assumptions, and then journey far beyond it to examine the dynamic, personalized strategies you need to build a resilient and fulfilling retirement.

Part 1: The Foundation – Understanding the 4% Rule

Before we can critique or move beyond the 4% rule, we must first understand what it is, where it came from, and why it became so influential.

What is the 4% Rule?

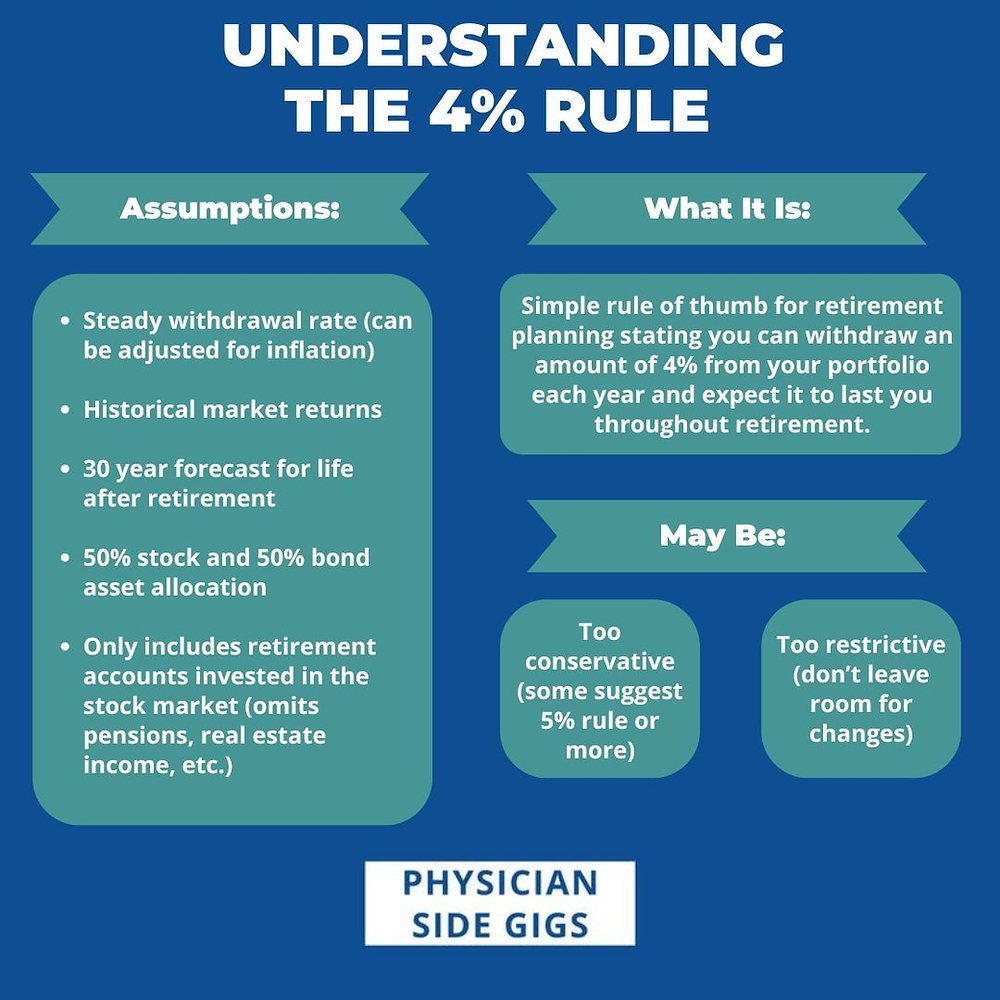

The 4% rule, also known as the “Safe Withdrawal Rate” (SWR) rule, is a guideline for retirement spending. It provides a simple answer to a complex question: “How much can I withdraw from my retirement savings each year without running out of money?”

The rule states that you can withdraw 4% of your initial retirement portfolio balance in your first year of retirement, and then adjust that dollar amount for inflation each subsequent year, with a high probability (historically, over 90%) that your money will last for 30 years.

The Calculation: A Simple Example

Let’s say you determine that you need $60,000 per year from your investments to cover your living expenses in retirement (excluding other income sources like Social Security).

Using the 4% rule, you would calculate your target retirement nest egg as follows:

- Annual Income Needed from Portfolio: $60,000

- Portfolio Target: $60,000 / 0.04 = $1,500,000

So, with a $1.5 million portfolio, you would withdraw $60,000 (4%) in Year 1. If inflation is 2% the following year, you would withdraw $61,200 in Year 2 ($60,000 * 1.02), and so on.

The Origin Story: The Trinity Study

The 4% rule gained widespread popularity from a 1998 paper by three finance professors at Trinity University. This research, now famously known as the “Trinity Study,” examined the historical success rates of various withdrawal strategies using market data from 1926 through 1995.

The study tested different portfolios (from 100% stocks to 100% bonds) and different withdrawal rates (from 3% to 12%). Its key finding was that a portfolio allocated 50% to stocks and 50% to bonds, with a 4% initial withdrawal rate adjusted for inflation, had a 95% success rate over all 30-year rolling periods within that timeframe. In other words, it worked in 95 out of 100 historical scenarios.

This provided a powerful, data-backed foundation for financial planners and individuals to build upon. It offered a semblance of certainty in an otherwise uncertain process.

The Critical Assumptions Behind the Rule

The 4% rule is a model, and all models are built on assumptions. Its historical success is contingent on several key conditions:

- A 30-Year Retirement Horizon: The 95% success rate is specifically for a 30-year period. For those who retire early at 55, a 40 or 45-year retirement is possible, which lowers the “safe” withdrawal rate. Conversely, for someone retiring at 70, a 4% withdrawal rate might be overly conservative.

- A “Traditional” Portfolio Allocation: The classic 50/50 or 60/40 (stocks/bonds) portfolio was the basis for the study. This allocation provided the growth of stocks with the stability and income of bonds.

- Consistent Annual Spending: The rule assumes you will take your inflation-adjusted withdrawal every single year, regardless of whether the market is up 30% or down 40%. It does not account for variable spending.

- Historical Market Returns as a Proxy for the Future: The rule is backward-looking. It assumes that future market returns (and the sequence of those returns) will resemble the past, particularly the strong bull markets of the 20th century.

Read more: Asset Location: 7 Tax-Smart Strategies to Supercharge Your Portfolio

Part 2: Moving Beyond the 4% Rule – The Critiques and Modern Realities

While the 4% rule is a brilliant starting point, the world has changed since the 1990s. Relying on it blindly ignores several critical modern realities that can significantly impact its effectiveness.

The Problem with Today’s Environment

- Lower Expected Returns: At the time of the Trinity Study, bond yields were significantly higher. Today, with bond yields still relatively low by historical standards, the “bond cushion” that helped portfolios recover from stock downturns is much softer. Many experts, including research firms like Morningstar, now suggest that future equity returns may also be lower than the historical average. Lower returns across the board mean a 4% withdrawal rate carries more risk today than it did in the past.

- Increased Longevity: People are living longer. A 65-year-old couple today has a nearly 50% chance that one will live to age 90, and a significant probability of one reaching 95. A 30-year time horizon may no longer be sufficient, requiring a more conservative spending approach or a more flexible strategy.

- Sequence of Returns Risk (SORR): This is arguably the single greatest threat to a new retiree’s portfolio. SORR is the danger that the order of your investment returns is unfavorable, particularly significant downturns in the early years of retirement.

- Bad Scenario: You retire with $1.5 million and the market drops 30% in your first two years. You’re still taking out $60,000 (plus inflation), but now you’re selling depreciated assets to do so. This permanently impairs your portfolio’s ability to recover, even if strong returns follow later.

- The 4% rule was stress-tested against historical sequences that included the Great Depression and the 1970s stagflation, but today’s high valuations and economic uncertainties mean SORR remains a paramount concern.

- Rising Costs, Especially Healthcare: Inflation is not a monolith. The 4% rule uses the general Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, costs for retirees, particularly for healthcare and long-term care, often rise much faster than CPI. A generalized inflation adjustment may not adequately cover these escalating expenses.

Is the 4% Rule Dead? The 3% and 3.5% Alternatives

Given these challenges, some financial analysts have argued for a more conservative starting point.

- The 3% Rule: A 3% initial withdrawal rate is significantly more robust. Using our previous example, to generate $60,000 annually, you would need a $2,000,000 portfolio ($60,000 / 0.03). This lower rate dramatically increases the success rate over longer time horizons and in lower-return environments. For those who are risk-averse or planning for a very long retirement, 3% is a much safer bet.

- The 3.5% Rule: This is often seen as a “sweet spot” compromise, offering a balance between safety and practicality. It would require a portfolio of approximately $1,714,000 to generate $60,000 per year.

The takeaway is not that the 4% rule is “dead,” but that it should be viewed as a ceiling rather than a floor. Starting at 4% is reasonable for many, but being prepared to be flexible—the core concept of the strategies we’ll discuss next—is essential.

Part 3: A Dynamic and Personalized Approach to Retirement Income

The most significant flaw of the static 4% rule is its rigidity. In reality, no retiree spends the exact same amount, adjusted only for inflation, every year for three decades. Life is variable. Modern retirement planning embraces this reality through dynamic and personalized strategies.

Strategy 1: The Bucket Strategy

The Bucket Strategy is a powerful mental and practical model designed specifically to mitigate Sequence of Returns Risk. It involves dividing your assets into separate “buckets” based on when you will need the money.

- Bucket 1: Short-Term (Cash & Cash Equivalents)

- Purpose: Cover 1-3 years of living expenses.

- Assets: Cash, savings accounts, money market funds, short-term Certificates of Deposit (CDs).

- Function: This is your spending money. By having several years’ worth of expenses in safe, liquid assets, you avoid being forced to sell stocks during a market crash to pay your bills.

- Bucket 2: Medium-Term (Bonds & Income Investments)

- Purpose: Cover expenses for years 4-10.

- Assets: Intermediate-term bonds, bond funds, CDs, and other conservative income-producing assets.

- Function: This bucket provides stability and modest growth. It is refilled periodically from Bucket 3 and, in turn, refills Bucket 1.

- Bucket 3: Long-Term (Growth Investments)

- Purpose: Fund your retirement beyond 10 years and provide growth to outpace inflation.

- Assets: Primarily stocks (equities) and other growth-oriented investments like real estate investment trusts (REITs).

- Function: This bucket is left to grow for the long term. During strong market years, you “take profits” and transfer money from Bucket 3 to Bucket 2 to replenish it.

The Benefit: The Bucket Strategy provides profound psychological comfort. During a market downturn, you can look at your devastated Bucket 3 and calmly say, “I don’t need that money for a decade or more. It has time to recover.” Meanwhile, you live comfortably off the safe assets in Buckets 1 and 2.

Strategy 2: Flexible Withdrawal Rules

Instead of a fixed, inflation-adjusted withdrawal every year, these rules introduce flexibility based on market performance.

- The Guardrail Strategy: Popularized by financial planner Jonathan Guyton and computer scientist William Klinger, this strategy sets upper and lower “guardrails” for your withdrawals.

- How it works: You start with a base withdrawal rate (e.g., 4.5%). If your portfolio performance is strong, your effective withdrawal rate (withdrawal/portfolio value) may fall. If it drops below a certain “lower guardrail,” you get an inflation increase. Conversely, if poor performance pushes your effective rate above an “upper guardrail,” you take an inflation cut.

- Example: Your portfolio shrinks due to a bear market, causing your withdrawal to represent 6% of the remaining balance (the upper guardrail). The rule would trigger, and you would forgo your inflation adjustment next year, or even take a small cut in your dollar withdrawal, to bring the rate back down.

- Simple Percentage-of-Portfolio Rule: Each year, you withdraw a fixed percentage of your current portfolio balance.

- How it works: Instead of a fixed dollar amount, you take 4% (or another rate) of whatever your portfolio is worth on December 31st of the previous year.

- Benefit: Your spending automatically adjusts to market conditions. In good years, you get a raise; in bad years, you tighten your belt. This guarantees you will never run out of money, but it also means your income is unpredictable.

Strategy 3: Integrating Guaranteed Income

A crucial part of modern planning is determining how much of your essential expenses can be covered by guaranteed, lifetime income streams. This creates a “floor” of income, reducing the pressure on your investment portfolio.

- Social Security: This is your most fundamental guaranteed income. The decision of when to claim it is critical. Claiming at your Full Retirement Age (FRA) or, better yet, delaying until age 70, can increase your monthly benefit by 8% per year delayed past FRA. This is often the most valuable “annuity” you can buy.

- Pensions: For those who have them, pensions provide a stable income base.

- Single Premium Immediate Annuities (SPIAs): You pay a lump sum to an insurance company in exchange for a guaranteed monthly income for life. While they lack flexibility and legacy potential, a SPIA can be an excellent tool to cover non-negotiable expenses like housing, food, and utilities, allowing you to take more risk (and seek more growth) with the remainder of your portfolio.

The Role of a Financial Planner

Given this complexity, working with a fee-only, fiduciary financial planner can be one of the best investments you make. They provide:

- Personalized Modeling: Using sophisticated software to run thousands of market simulations (Monte Carlo analysis) on your specific portfolio and spending plan.

- Tax-Efficient Strategy: Helping you decide which accounts to withdraw from first (e.g., taxable, tax-deferred, tax-free) to minimize your lifetime tax burden.

- Behavioral Coaching: Their most valuable role may be to stop you from making emotionally-driven financial mistakes, like selling all your stocks in a panic during a market crash.

Part 4: Crafting Your Personal Retirement Number

So, how do you bring all of this together to find your number? It’s a multi-step process that moves from the general (the 4% rule) to the highly specific (your dynamic plan).

Step 1: Estimate Your Annual Retirement Expenses

This is the most important step. Be detailed. Categorize your expenses:

- Essential: Housing, utilities, food, healthcare, transportation.

- Discretionary: Travel, hobbies, dining out, gifts.

- Intermittent: New car, new roof, major travel.

Step 2: Identify All Your Income Sources

- Pensions

- Part-time work

- Rental income

Step 3: Calculate the Gap

- Total Annual Expenses – Total Annual Guaranteed Income = Annual Gap to be Filled by Your Portfolio

Step 4: Apply a Conservative Withdrawal Rate

- Given today’s environment, using a 3.5% or 3.25% rate is prudent. Let’s use 3.5%.

- Your Target Portfolio = Annual Gap / 0.035

Example:

- Desired Annual Spending: $80,000

- Social Security & Pension: $35,000

- Annual Gap: $45,000

- Target Portfolio (using 3.5%): $45,000 / 0.035 = $1,285,714

This number, ~$1.3 million, is your initial target based on a static rule. Now, you layer on the dynamic strategies.

Step 5: Stress-Test and Personalize Your Plan

- What if you retire early? Use a lower withdrawal rate (e.g., 3.0%).

- What’s your risk tolerance? Consider implementing a Bucket Strategy.

- How flexible are you? Could you reduce spending by 10% in a bad market year? If so, your success probability skyrockets.

- Run scenarios with a planner or a good retirement calculator.

Conclusion: Principles for a Confident Retirement

The journey to “your number” is not about finding a single, magical figure. It’s about building a flexible, resilient system. The 4% rule is not a destination, but a valuable landmark on your map.

The most successful retirees understand that retirement planning is not a “set-it-and-forget-it” task. It is an ongoing process of monitoring, adjusting, and adapting. By combining the foundational wisdom of the 4% rule with dynamic strategies like bucketing, flexible withdrawals, and guaranteed income, you can move forward with confidence, ready to enjoy the retirement you’ve worked so hard to achieve.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I’ve heard the 4% rule is outdated. Should I just use 3% instead?

A: While a 3% withdrawal rate is undoubtedly safer, especially for longer retirements or in low-return environments, it may also be unnecessarily conservative for some, requiring a much larger nest egg. A better approach is to use 4% as a rough initial planning benchmark but build a plan that includes flexibility. Being prepared to spend a little less in down markets can allow you to safely start at 4%, whereas a rigid 3% plan might mean you worked longer or saved more than was strictly necessary.

Q2: How does the 4% rule work if I retire early, say at 55?

A: For early retirement, the standard 4% rule becomes riskier because your money needs to last 40-50 years. Most financial planners recommend a more conservative initial withdrawal rate for early retirees, typically in the 2.5% to 3.5% range. This is where dynamic strategies like the Bucket Strategy become especially critical to manage the heightened Sequence of Returns Risk over a longer time horizon.

Q3: Does the 4% rule include my Social Security and pension income?

A: No, and this is a common point of confusion. The 4% rule is applied only to your investment portfolio (e.g., 401(k), IRA, brokerage accounts). You should first calculate your total retirement expenses and then subtract your guaranteed income (Social Security, pension) to determine the “gap” that needs to be filled by your portfolio. The 4% rule is then applied to that gap to find your target portfolio size.

Q4: What’s a better alternative to the 4% rule?

A: There isn’t one single “better” alternative that fits everyone. The most robust approach is a combination of strategies:

- Use the Bucket Strategy to manage sequence risk.

- Implement a flexible withdrawal rule (like the Guardrail Strategy) that allows you to trim spending slightly in bad markets.

- Use guaranteed income (Social Security, SPIAs) to cover your essential expenses.

This multi-pronged approach is far more adaptive and resilient than any single, static rule.

Q5: How should I adjust my withdrawals for inflation?

A: The classic 4% rule uses the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). In your personal plan, you should focus on your personal inflation rate. The costs that tend to rise fastest for retirees are healthcare and housing. It may be prudent to use a slightly higher assumed inflation rate for your essential expenses (e.g., 3%) when doing long-term planning, rather than the general CPI-U, which may be lower.

Q6: What asset allocation should I have in retirement?

A: There is no one-size-fits-all answer, as it depends on your risk tolerance, time horizon, and other income sources. However, being too conservative (e.g., 100% bonds) is a major risk, as your portfolio may not grow enough to outpace inflation over a 30-year retirement. A traditional allocation of 40-60% in stocks is common, with the remainder in bonds and other assets. The Bucket Strategy naturally creates a layered allocation, with your short-term buckets in cash and your long-term bucket heavily in stocks.